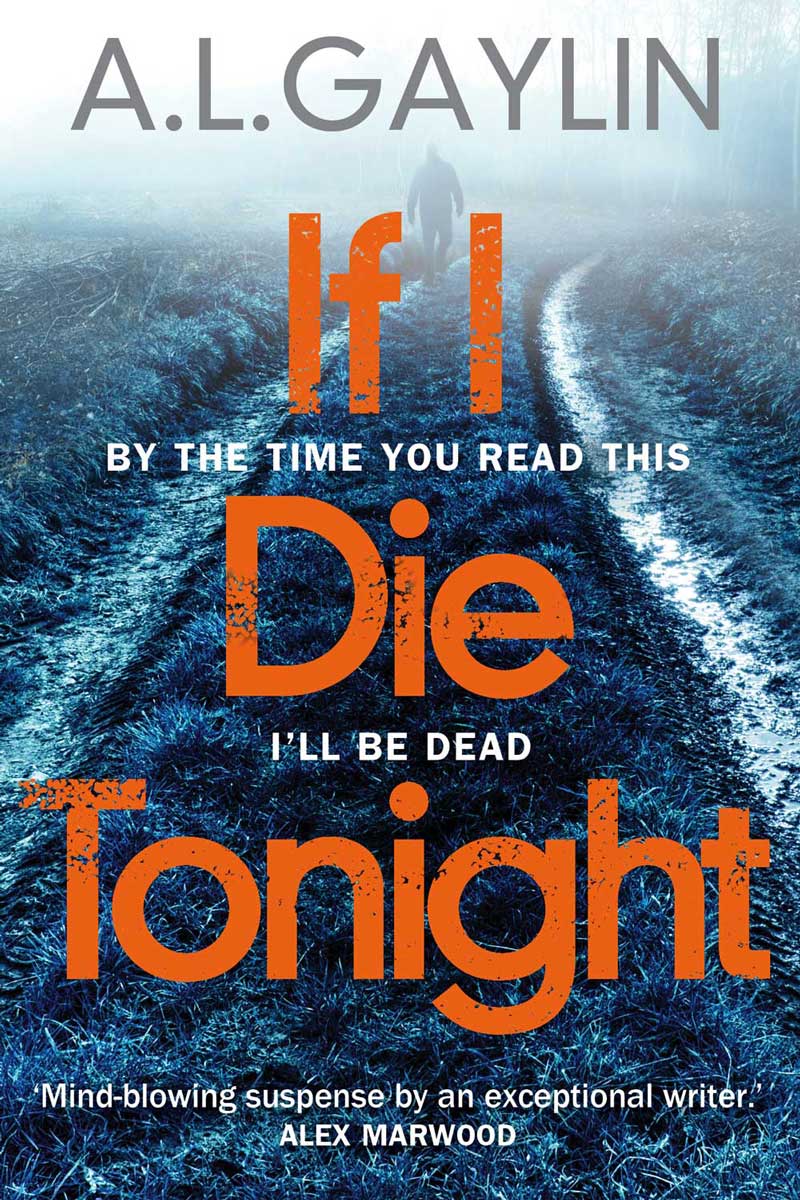

IF I DIE TONIGHT

Prologue

From the Facebook page of Jacqueline Merrick Reed.

October 24 at 2:45am

By the time you read this, I’ll be dead.

This isn’t Jackie. It’s her son Wade. She doesn’t know where I am. She doesn’t even know I can get on her FB page, so don’t ask her.This isn’t her fault. I am not her fault.

I am writing to tell my mom and Connor that I’m sorry. I never meant to hurt anyone. I wish I could tell you the truth of what happened, but it’s not my truth to tell. And anyway, it doesn’t matter. What matters, what I want you both to know, is that I love you. Don’t feel sad. Everything you did was the right thing to do. I’m sorry for those things I said to you, Connor. I didn’t mean any of it.

Funny, I’m thinking about you right now, Connor. How you used to follow me around all the time when you were a little kid. How you used to copy everything I did.You probably don’t remember this but when you were about four, I taught you the middle finger, and you did it to that mean babysitter we had.What was her name, Mom? Loretta? Lurleen? Anyway, Whatever-her-name-was had some crap reality show on the TV. Real Housewives of the Seventh Circle of Hell. She wouldn’t let us watch the Mets game and called us nasty little brats and told us we had no business talking at all because children should be seen and not heard.Whatever the hell that’s supposed to mean.

So, Connor gets off the couch, walks up to Lurleen and flips her the bird. He was so little, he needed two hands to do it. He used the left hand to hold down the fingers on the right. Do you remember this, Mom? Because I’m pretty sure she ratted us out without explaining the context of forcing us to watch her crap TV show. You were so mad, we didn’t get dessert for two weeks.

I remember thinking how unfair the whole thing was and how quick grown- ups were to believe the lies of other grown-ups, especially when it came to their own kids. But looking back on it now, all I can remember is how red Loretta’s face got and how hard we both laughed, even with her shrieking at us. It was one of those moments. My English teacher Mrs. Crawford called them ‘memory gifts.’You keep them in a special part of your brain and you kind of wrap them up to preserve them and tie them with a ribbon, so when you need them, when you’re feeling really bad, you can unwrap them and you remember all the details and feel the moment all over again. So thanks for that memory gift, buddy. It’s making me smile now.

I’m all alone here right now, unless you count the ghost lol. I’m writing this just after taking the pills, but I won’t post it until I start to really feel them. According to what I read, death comes pretty soon after that.

So I’m typing extra fast. Sorry about typos.

This will probably make a lot of you very happy. Good. For anybody who might be sad, sorry. But you know what? Stuff happens.Things go wrong.And the more you stick around, the wronger they get. I know I’m just 17. But I think of what life would be like if I wasn’t here. I think of the way things could have gone without me in the picture, how much better it would be.And then I know. I’m sure of it. I’ve lived too long already.

1,043 people like this

ONE

Five days earlier

In bed late at night with her laptop, Jackie Reed sometimes forgot there were others in the house. That’s how quiet it was here, with these hushed boys of hers, always with their heads down, with their shuffling footsteps and their padded sneakers, their muttered greetings, their doors closing behind them.

When did kids get to be so quiet? When she was their age – well, Wade’s age anyway – Jackie clomped around in her Doc Martens and slammed doors. She’d blast her albums loud as they’d go – Violent Femmes and Siouxsie and Scraping Foetus off the Wheel – edging up the volume until her bones vibrated with the bass, the drums, flailing around her room, dancing as hard as she could with her parents pounding on the walls, begging her to turn it down.

Please, Jacqueline, I can’t hear myself think!

Looking back on it now, she saw it as a rite of passage, the same one her mother had gone through with her Elvis and her Lesley Gore, and her grandmother too, no doubt, cranking the Mario Lanza as though she was the only person who mattered in the cramped Brooklyn walk-up where she grew up.

There was such power in loud music, such teenage energy and rebellion and soaring possibility. Who’d have thought, back then, that it would all go extinct within just one generation? These days, teens plugged themselves into devices, headphone wires spooling out of their ears like antennae. They kept their music to themselves, kept everything to themselves and their devices and the friends they talked to on those devices, all of whom you couldn’t hear, couldn’t see unless you swiped their phones away mid-conversation to read the screen and who wanted to do that? Who wanted to be that mom ?

They shut you out. Your children shut you out of their heads, their lives. And that was a form of rebellion so much more chill- ing than blasting music or yelling. They made it so you couldn’t know them anymore. They made it so you couldn’t help.

Just yesterday, she’d been making breakfast when Wade’s phone had gone off like a bomb on the kitchen counter. That incoming text tone of his, literally like a bomb, the sound of an explosion. When and why did he download that? Jackie had nearly jumped out of her skin, spattering bacon grease, hand pressed to her heart . . .

The phone’s case was missing – an accident waiting to happen, the latest broken screen of so many broken screens in this house. Why didn’t her boys take better care of their things?

Moving it back from the edge of the counter, Jackie had looked. The text had been from someone he’d nicknamed simply ‘T’: Leave me alone.

The gut-punch of those words, the intimacy of the single initial. Who was this person? A girl? How could she say that to Wade? What has he done? All those questions looping through her mind. And here, a day later, Jackie still didn’t know the answer to a single one of them.

Once Wade had retrieved his phone and left for school, she’d checked his long-abandoned Facebook page for cryptic posts from friends with T names and dusted his room for evidence of a girlfriend – but not too deeply. She couldn’t bear to hack his laptop or go through his drawers. She wasn’t that mom.

Casually, in the car on the way to his guitar lesson, she’d asked Connor, ‘Do you know if Wade has been fighting with any of his friends?’

Connor had shaken his head and replied quietly, saying it to the car floor in his cracking, changing thirteen-year-old voice, ‘I don’t really know too many of Wade’s friends, Mom.’

Jackie sighed. She and Wade needed to talk. But not now. It was nearly midnight and his third and final chance at the SATs was tomorrow and he needed his sleep. Wade was looking so tired lately, she wondered if he ever really slept at all.

Jackie felt a chill at her back, cold night air pressing against her bedroom window, against the thin walls, creeping through cracks in the plaster. Her house was so drafty, even now in mid-October. She hated thinking about what the winter would be like. A lifetime ago, Jackie had lived in sunny Southern Cal- ifornia. The Hollywood Experiment, she and her ex-husband Bill had called it, when they were still young and childless – not even married yet, Bill with his screenplay, Jackie with her half-finished novel, driving out to LA to follow their dreams. It had only lasted a year, the Hollywood Experiment coming to a crashing close when Jackie had gotten pregnant with Wade and they’d moved back to Havenkill, where they both were assured real jobs. But what a warm year it had been, in every way. Those breath-hot Santa Ana winds on the back of her neck, the camellias blooming bright, all the way into Christ- mas. In twelve months, Jackie hadn’t needed to unpack a single pair of socks and they’d slept nude, crisp sheets against their skin . . .

Jackie pulled the comforter tighter around her and focused on her laptop screen – the scrolling Facebook feed with its lurid shots of five-star dinners, vacations in St. Bart’s, Miami, the Mexican Riviera, perfect cocktails brightened up with exotically named filters. Perpetua, Valencia, Clarendon.

So many selfies, too. One caught Jackie’s eye: her friend Helen Davies, who worked with her at the Potter Bloom real estate agency and had gone to high school with her thirty years ago in this very town. Helen with her chunky gold earrings and her Mona Lisa smile, head tilted down, ducking the camera in the same way Jackie did, that middle-aged female way, hoping for low light. But Helen looked so much livelier than Jackie, so much more satisfied, her peachy-skinned, seventeen-year-old daughter Stacy thrust in front of her like the lovely feature she was.

Girls’ day in the city, the caption read. Shopping at Saks!

Jackie looked at Stacy’s bright smile and felt a stab of jeal- ousy. Did they know their children better than she did, these mothers of daughters? Were they as happy as they looked?

Stupid question. Nobody was as happy as they looked on Facebook – even Jackie knew that. She reached for her glass of Chardonnay and took a long swallow, feeling the comforting tart- ness of it at the back of her tongue, the warmth as it slid down her throat. She glanced down at the corner of the screen: 11:27 pm. Time to sleep. Or try to. Why did her brain do this to her every night? She’d wander through her whole day exhausted, and then as soon as it was time to go to bed, all of the worries and misgiv- ings she’d successfully buried during the past sixteen hours would pop out of their shallow graves, one by one, and parade through her brain, keeping her awake. Memories, too. Like the time she was showing her very first house and the couple got the time wrong and she wound up half an hour late at Wade’s pre- school to find him sitting on the bench in the parking lot, his little face pinched red, teacher dabbing at his tears.

Mommy, where were you? Did you forget about me?

Jackie slid open her nightstand drawer, found her bottle of Xanax. She took half a pill – just half, washed down with the rest of the Chardonnay. By the time she’d quit out of Facebook, closed the laptop screen and flicked off her light, her breathing had slowed and she felt herself sinking into a velvety half-sleep, her muscles relaxing. Jackie closed her eyes and drifted off, drowsy and warm with the knowledge that everything in life was temporary, life included. And really, when it all came down to it, nothing was worth the effort it took to worry.

A sound jolted Jackie awake; she wasn’t sure what. She’d been dreaming she was in a rowboat in the middle of choppy waters and the oars wouldn’t reach, and when she woke, she felt queasy from something, either the dream or the Chardonnay. It took her several seconds to blink the cobwebs out of her brain and focus on the sound, which was coming from across the hall – a scuf- fling, the clink of metal. She reached for her phone; 911, she thought. Call 911. No. No, breathe first. Listen. Could be the wind. Could be anything.

Jackie breathed. Three deep breaths, what Helen called cleans- ing breaths, Helen and her yoga classes, out with the bad energy, in with the good. She tried to focus on the scuffling, really hear it. She exhaled again, hard; air tumbling out of her. Listened.

Arnie. Connor’s pet hamster, racing around his cage. Noctur- nal or not, that animal slept all the time . . . What woke him up?

From down the hall, near the front door, Jackie heard the creak of floorboards. A thump. She bolted up to sitting. Looked at the digital clock on her nightstand: 1:48 am.

Heart pounding up into her throat, Jackie grabbed her phone, crept toward the bedroom door, bare feet on the hardwood floor, heel to toe, heel to toe, breath soft and shallow, arms straight out like a tightrope walker . . . Don’t make a sound.

She pressed 911 on her phone, her finger hovering over the send button. If she saw anything, anyone . . . She cracked the door. Don’t hurt my boys, she thought. As though they were smaller than her. You hurt my boys, I’ll kill you.

Jackie peered into the darkened hallway.

Behind Connor’s closed door, Arnie squeaked and shuffled in his cage.

Jackie kept a baseball bat by her bedroom door. Left over from Wade’s long-forgotten Little League days. She took the bat in hand, the cool metal against her palm calming her.

She moved into the hallway. ‘Hello,’ she said. ‘Anyone there?’ Jackie flipped the hall light on. She glided across the hall to Connor’s room, bat and phone in the same hand. With the other, she cracked the door. The room was warm, pitch-dark, heavy with the sound of her son’s sleep-breathing, Arnie’s insistent squeaks. Her eyes adjusted. No one in here but the two of them.

She lowered the bat, her heartbeat slowing as the last shards of sleep fell away and everything grew clear. Okay, she thought. This is what’s going on. She backed out of Connor’s room. Softly closed his door.

Wade’s door was ajar, and she knew without looking that the bed would be empty, that the thumps she’d heard earlier had been the sound of someone leaving the house, not breaking in. From where she was standing, she could see him through the long window next to the front door, the shadow of him in the porch light. A few steps closer and she saw him in full. Wade. His back to the house, the glow of his cigarette. Watching the stars. When did he get so tall?

Jackie should stop him, she knew. He needed to sleep. He shouldn’t be smoking. She knew all of that. But she couldn’t.

Let him have this.

Jackie slipped back into her own room, slid open her night- stand drawer and took the other half-Xanax, this time with nothing. She pulled the comforter up to her chin and closed her eyes, waiting for the calm. As she started to drift, she found herself thinking of Wade. How smiley and talkative he’d been when he was little, so eager to please. He was different now. A different boy, a sad boy . . .

No, sad was the wrong word. Sad was something she understood.

Pearl Maze was on the phone with the drunk’s wife when the rain started.

‘I’m sorry, ma’am,’ Pearl was saying, eyes on the drunk, head- ache starting to blossom. ‘But we can’t just hold him here indefinitely.’

‘Isn’t that what they’re for?’ the wife said. ‘Holding cells? I mean, Jesus. It’s nearly three in the morning. Why should I have to suffer for his idiocy?’

‘We don’t have a holding cell, ma’am,’ she said. ‘We’re too small for a holding cell. We just have a holding bench.’

The drunk was cuffed to the bench. His head lolled to one side and his eyes were half-closed and his mouth open, drool trickling out the side of his clean-shaven face and into the collar of his pink-and-white-striped, Oxford-cloth shirt. The drunk did have a name, though Pearl didn’t see the point in remembering it, him losing consciousness and all. She’d typed it into the computer and fingerprinted him after Tally and Udel had brought him in, kicking and screaming that he’d committed no crime, that he hadn’t been driving, he’d been enjoying the evening for chris- sakes and looking up at the stars and what the hell did they mean, disturbing the peace, disturbing the peace was his God-given right as an American, you’re all worse than my wife, you know that?

The drunk wasn’t from around here – he was visiting from New York City. A leaf peeper, staying at the Pine Hollow B & B with his incredibly put-out-sounding wife. Pearl was over and done with the both of them. Go back to New York City. I’ll pay for your train tickets. The whole booking room stunk of him now – whiskey and stale cigarettes and whatever else he’d rolled around in between consuming eleven Jamesons and a beer chaser at the Red Door Tavern and sitting cross-legged in the middle of Mer- chant Street, yelling obscenities at the flashing traffic light. The smell wasn’t doing anything to relieve her headache. Pearl shut her eyes and squeezed the bridge of her nose. She needed a glass of water, two cups of coffee, three Advil.

‘All right, fine,’ said the wife. ‘I’ll be right over.’ ‘Thank you.’ Pearl hung up. Thank you, Jesus.

The drunk said, ‘She coming?’ Pearl nodded.

He nodded back at her. Then he leaned over and threw up all over the booking-room floor.

‘Beautiful.’ Pearl jumped up from the desk and hurried into the break room to get paper towels and water and away from the drunk. That was when the sky opened up. Could this night get any better?

‘What happened in there?’ Bobby Udel said it as though he couldn’t care less. He said everything as though he couldn’t care less. Udel was one of the younger officers, about Pearl’s age. Nice enough, she guessed, but to her mind he was suspiciously mellow for a cop. He’d grown up in this town. Maybe that had something to do with it.

Pearl looked at him – those watery blue eyes, that weak, little boy’s chin. Cradling a mug with a map of New York State on it in smooth cherubic hands. She felt old enough to be his mother. ‘You don’t want to know.’

He chuckled. ‘Jim Beam tossed his cookies, huh?’

Pearl found a bucket and started to fill it in the sink. ‘Jim Beam,’ she said. ‘That’s a good one.’ She grabbed a glass out of one of the cupboards, held it under the running faucet and gulped it down. The rain drummed on the roof. It made her heart pound. Any day now, she thought. Any day the roof will cave in . . .

Pearl had known about the structural damage since she took this job. All the cops joked about it because what else are you going to do? In keeping with the rest of Havenkill, which was more often than not referred to as Historic Havenkill, it was a charming building to look at – bright blue shutters, brass door knocker. Window boxes even, as ridiculous as that may sound. But it was also condemned. A lovely shell of a place, falling apart for years, though Hurricane Irene had pounded the final nail into its coffin. ‘The Death Trap,’ the sergeant called the station. ‘The Busted Bunker.’ The hardwood floors buckled and popped; wind whistled through gaps in the doorjambs. And on rainy nights like this, the ceilings bled out in dozens of places. Pearl could see a spot now, right at the center of the break room, dripping angrily, water spattering on the floor. Less than two weeks, and the Havenkill PD would break ground on a new station, Pearl and her fellow officers moving into a double-wide in the new parking lot. Closer quarters, but much safer ones, especially considering the nasty winter the weather people kept predicting. Keep it together, Busted Bunker . . . Just nine and a half more days . . .

A gust of wind knocked into the side of the building, the rain thudding now. Hammering. She ripped off a swath of paper towels, grabbed the full bucket, a bottle of Murphy’s oil soap, a mop out of the janitor’s closet. The puke is fixable. Focus on that.

‘Need any help?’ Udel said in his half-hearted way. Pearl shook her head. As she headed down the hall on her way back into the booking room, she was certain she could hear the creak of shingles detaching. ‘The drunk was slumped on the bench, snoring. Holding her breath, Pearl poured some of the water from the bucket onto the mess he’d made, and followed it up with a few squirts of cleaner. It roused him a little. ‘You don’t know,’ he murmured at her.

‘Huh?’

His eyes opened. ‘You’re young,’ he said. ‘Just a kid. You don’t know yet how pointless life is.’

She stared at him for a few seconds, remembering his name. ‘You’re wrong about that, Mr. Fletcher.’

‘Shit,’ he said, not to Pearl but at the explosion of noise – a furious pounding on the front door and then the buzzer, someone leaning on it so hard it was as though they wanted to break it.

‘That doesn’t sound like your wife, does it?’

He shook his head.

Pearl rushed toward the door, Udel, Tally and then the ser- geant leaving his office, moving in front of Pearl, pressing the intercom and trying to talk to her, the woman on the other side of the door, trying to calm her as she half-screamed, half-cried like women never did on the quiet streets of this historic Hudson Valley town. ‘Please, ma’am,’ the sergeant said. ‘We are going to let you in.’

But she didn’t seem to hear. ‘An accident.’ That was all she kept saying, over and over again, even after he opened the door for her and she fell through it – make-up smeared, weeping in her bright red raincoat and rainbow-dyed hair, wet as something dredged up from the river. ‘There’s been an accident.’

‘Mom?’ Connor called out from the kitchen.

Jackie couldn’t answer. She was in Wade’s doorway, eyes fixed on his empty bed.

‘Mom!’

Jackie swallowed hard and made her way into the kitchen. It smelled of the coffee she’d set to brew last night.

‘Can you take me to Noah’s house?’ Connor said it around a mouthful of cereal. He was sitting at the kitchen table, back turned to her, eating fast. ‘I’m gonna be late.’

Jackie said, ‘I thought Wade was taking you.’ ‘I . . . He said he didn’t have time.’

‘He said that.’ ‘Yes.’

‘This morning.’

‘Yes, Mom.’

‘It’s ten.’ She said it slowly, staring at the back of his head. ‘Why didn’t he have time? The SATs don’t start till eleven thirty.’ Connor shrugged elaborately. ‘How do I know? I just need a ride.’ The word ride pitched up an octave. The back of his neck flushed red. Poor kid, voice constantly betraying him. Puberty was cruel and, for Connor, it often proved a lie detector, his voice cracking more than usual during those still-rare attempts to be

deceitful.

‘Connor.’

‘Yeah?’

‘Did Wade come home last night?’ ‘What?’A thin squeak.

‘It’s a simple question.’

‘Mom, if I don’t leave for Noah’s, like, now, we won’t have enough time to work on our science project.’

‘Did you see him?’ Jackie said. ‘Did you see your brother this morning?’

‘Yeah, of course I did.’ He said it quietly, carefully. ‘He was leaving when I got up.’

‘Look at me.’

Connor turned around. He blinked those bright blue eyes at her, his father’s eyes. ‘Mom,’ he said. ‘Are you okay?’

Jackie swallowed. No, she wanted to say. I’m not okay. I used to know you guys so well I could read your thoughts, and now it’s as though every day, every minute even, I know you less. You’re turning into strangers.

You’re turning into men.

She looked at the half-empty coffee pot, the demolished bowl of cereal placed next to the sink, unemptied, unwashed, a few stray Cheerios swimming in puddled milk. Wade never washed out his cereal bowls. Connor did. Wade drank coffee. Connor did not. Wade had been here this morning, she decided. Last night, he’d had his moment on the front step with his cigarette and the stars, and then he’d come back inside. He’d gone back to bed, gotten up this morning and left early, for whatever reason. Connor wasn’t lying. Connor didn’t lie. Not about anything big, anyway.

‘Mom?’

‘I’m fine.’ ‘You sure?’

She cleared her throat. ‘Maybe after I get home from work, you and Wade and I can do something.’

Connor looked at her as though she’d just sprouted a third eye. ‘Umm.’

‘Maybe go out to dinner. See a movie? Talk?’

He blinked at her again. ‘Sure,’ he managed after a drawn-out pause during which they both locked eyes, a type of standoff.

Jackie smiled. It was natural, she knew, this aching feeling, this growing divide between the boys she raised and herself. All those books she used to read, the shrink she used to go to, all of them told her that as a single mother of sons she needed to maintain distance, to teach them to stand on their own early, lest they grow up too dependent on her, too possessive. Nobody liked a mama’s boy. But still, that didn’t make it any easier, your baby wincing at the thought of spending time with you.

‘Go get your stuff, and I’ll take you to Noah’s.’

Connor propelled himself out of the room.

Jackie went to the sink, spilled the milk and cereal out of Wade’s bowl and rinsed it, thinking about all the times she’d yelled at him to rinse his bowl, how carefully she’d explained to him that if he didn’t wash it out right away, the cereal would crust on and never come off, no matter how many times she put it through the washer. She’d shown him the evidence: the scarred, ruined bowls, cereal remnants clinging to the sides like cement. Wade would nod at her, that dyed black hair of his flopping into his eyes, but it never sunk in. Or maybe he ignored her on purpose, the same way, without warning, he’d blackened the sandy-blond hair that used to match her own. The way he’d taken his phone the day before yesterday, checking his texts without looking at her. And how he’d said, ‘See you later, Mom,’ in that calm, unreadable voice, without making eye contact, without looking at her at all.

It was normal, the way the boys treated her, the way they made her feel. Growing up was hard and parents bore the brunt of it, mothers especially. Mothers of teenage sons.

It is normal, she thought. Isn’t it? And then the doorbell rang.

The police.